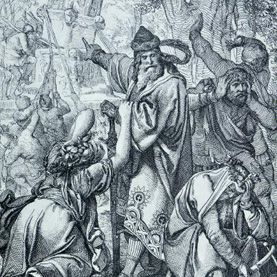

Charlemagne attacking the pagans in Saxony

You might be getting tired of a history lesson. It is important for our life together, I believe to figure out how we got to where we are. We have asked the question as to what happened to the missionary zeal of the early church? Why is Luther said to have had no theology of Missions and how did Christianity get to a point where preaching the Gospel to pagans was considered by some to “reverse the order of Nature”? Why do we continue to hear from some in our congregations statements like – “those people are beyond our mission (parish) boundaries”, or “what are people like that (you name what “that” is) doing in the church in the first place”? My favorite is still – “don’t we have a mission here too?” That is usually the preamble to cutting off funds for a mission that is somewhere else.

I said in a previous blog that evidence exists that the pagan Germans who tried to destroy the Roman Empire really carried Christianity into the farthest reaches of the known world. By the year 1000 Christian churches were planted from Greenland to China. Christians existed in India and parts of Asia as well, although those churches were established by direct Apostolic contact rather than by new convert zeal. But it is the Germans that we are interested in because they bear a direct connection to our discussion. Saxony is really the birth place of the Lutheran Church Missouri Synod so let’s go there.

Hermann Arminius, a Cheruski German, thwarted the ambitions of Emperor Augustus to extend the Roman Empire beyond the Rhine to the Elbe. In a decisive encounter in 9 CE at the Teutoburger Wald near Luegde, he defeated the Roman Army. In consequence, the German people in the region of Saxony were to be isolated from the diffusion of Christianity that was occuring throughout the Roman Empire from the 3rd C on. In the eight century the Carolingians emerged as the new ruling family of the Frankish world. Under the leadership of Charlemagne (742-814, otherwise known as Karl der Grosse, Saxony was finally incorporated into the Frankish Empire. It took many military campaigns extending over a thirty-year period to conquer and convert the pagan Saxons.

“From his perspective as a Christian King with a God-given responsibility to sustain the church in its mission of saving souls, religious life was a prime factor in sustaining concord and justice. He encouraged the spread of Christianity…even using force to compel reluctant pagans, such as the Saxons, to receive baptism.”

Quoted from A Short History of Western Civilization by Harrison et al.

So leaders and Kings got into converting folks to Christianity as did Constantine and Charlemagne. Many more come to us from history. They have great names too. Clovis and Boris Tryggvason, his brother Olaf, Ethelbert, Widukind, to name a few rulers that were into converting. We could say they were into ‘missions”. They took seriously the Great Commission. One man with the particularly evocative name of Harald Bluetooth claimed to have “made the Danes Christian”.

So here is the question that Fletcher is trying to find an answer for and a derivation of which I am desperately trying to understand – What did these people actually do? What did conversion mean to them and the people that they “made” Christian? Fletchers idea is that it was certainly not a “reorientation of their souls” although that might have come later after some form of catechesis. Words used for conversion meant “submitting to or accepting” rather than “receiving”. For Fletcher, and you may choose to disagree with him, conversion seems to be more of an acceptance of a “body of Christian observance”, rather than a reception of Christ. More of a submission to a way of life rather than a personal trust in Christ as Savior. Now that could have come later, after all one has to start somewhere, but for all intents and purposes it was not preaching the Gospel to every creature and baptizing as much as it was a cultural domination. A rather nasty dislocation of the Saxon Society for a more ordered Christian one is certainly pictured in the wood carving above. In todays language we might call these people “mercenary converts”, they switched sides as it were for a better life. Did they mean they had no faith? Not necessarily. The question has to be asked because as Fletcher says, “An impious age such as that in which we live is apt to be embarrassed or bewildered by the concerns of more pious epochs”.

Did these people convert out of submission to a higher authority or because of a deep conviction of the heart, and if it was the former what does that say about us? There were pious and deeply faithful people in the church after the first centuries of Christianity, but we are talking about a church that was beginning to loose it’s first love and become an “institution” that had commercial and political viability. Generations of people were Christians because as my little cousin used to say, “they were borned that way”. How many of our brothers and sisters are Christian by birth only and does it make any difference? Had I not been raised by Christian parents and baptized at an early age would I have come to faith? More germane to our discussion, would anyone have brought the faith to me? If my name were Bernie Ogonganyo and I was black and from East Africa living in America, would anyone from the Smallenburger Church downtown have told me about Jesus?

I am enjoying the history lesson. Interesting! Thanks, Cheryl